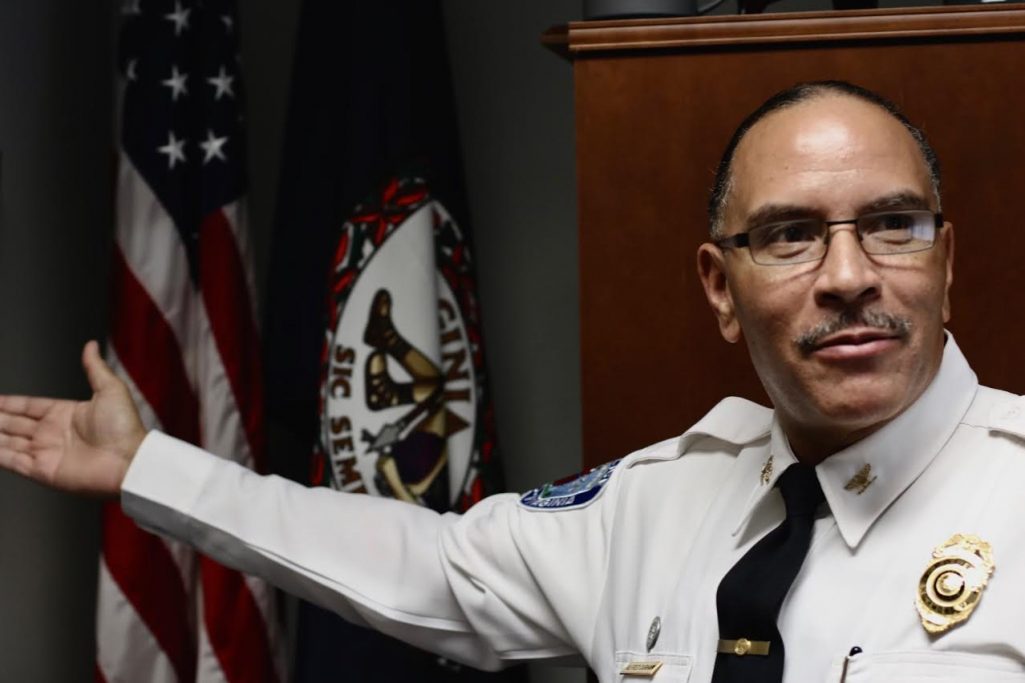

Between an epidemic of shooting deaths and fears of a Charlottesville-like riot, 2017 was a tough year for the city, but it posed a unique challenge for Chief of Police Alfred Durham. As of Dec. 1, 57 Richmonders have lost their lives to gun violence, and the city spent $570,000 to respond to the tiny rally organized by a ragtag group of neo-Confederate activists from Georgia and Florida.

Other challenges included controversy around a parking policy aimed at curbing crime in city housing projects, and a statement linking marijuana to the homicide rate. Our political director, Landon Shroder, and I sat down with Durham to hear his take, over a candid, far-ranging discussion in his office at police headquarters.

In person, Durham was as blunt and straightforward as he is at the podium. “I’m just a straight shooter. I’ve always been,” he said, describing it as part of the job. “You have to be direct, and you have to tell the truth. My integrity is all I have. If people don’t have trust in the chief, the department is going to fail.”

Durham seeks to build integrity and trust through a dual approach of increasing community policing initiatives, and systemic reform targeting misconduct. The latter was a top concern before he agreed to come back to Richmond as chief in 2015.

Policing Reforms

“I was adamant about [addressing misconduct] coming in,” Durham said. He describes the shooting of Michael Brown as a catalyst for necessary reforms. “August 9 changed the way policing is done in the United States. That was the incident that woke the sleeping dragon.”

I made it clear we’re going to treat people with fairness and respect. We work for them.

His approach started with a focus on transparency and outlining a clear vision for the department. “I made it clear, we’re going to treat people with fairness and respect. We work for them, they don’t work for us,” he said. One of the first policy changes he implemented was a requirement that employees report any policy violations they are aware of before clocking out.

Requiring everyone from dispatchers to officers to file reports helped, but he had to convince citizens to complain, too. “When I go to meetings, I ask folks, ‘You say this happened, why didn’t you file a complaint?’” The response he kept getting was cynical. “[They say] ‘well, you’re not going to do anything anyway.’”

When he asked people why they wouldn’t give him, a new chief, a chance to address the complaints, it came down to the difficult filing process that required the complainant to drive to a precinct and sit around waiting to give a statement. He enacted a new policy immediately. “If you feel that you’ve been mistreated by a police officer or did not receive the service you deserved, you call a supervisor to the scene right there.”

He credits the new policy with a reduction in citizen complaints, from 99 incidents under investigation in 2014, to only 37 as of Nov. 15 in 2017.

It was data that first suggested the issue. When Durham reviewed the 2014 numbers from internal affairs, he said he “saw a disparity in the number of citizen complaints versus the internal [reports]. Internal [reports are] recognizing that there has been some type of violation or misconduct.” When internal reports are low and citizen complaints are high, it can be an indicator that misconduct isn’t being addressed, he said.

“Today, our numbers have flipped,” he said, pointing to metrics that suggest the policy changes worked. “Almost 75-80 percent of the time, the situation was resolved [on the scene],” he said, referring back to the policy of calling a supervisor at the scene when a citizen has a complaint.

In a city with 200,000 or more calls for service per year, 37 seems like a low number, but Durham said there was still work to do. “We don’t always get it right because even when we stop somebody in a contact or even on a traffic stop we have to tell them why we stopped them,“ he said, giving an example of a type of minor conduct violation that generates complaints.

The big decrease may also be part of his pivot to cover the changing role of the police. “We’ve trained almost 85 percent of our officers to be what we call crisis intervention teams. We’re teaching de-escalation,” he said, referring to the increasing role police play in responding to people with mental health issues, juveniles in school systems, and even just someone having a bad day.

Community Policing and Youth Outreach

For some crime, he thinks an arrest may cause more problems. “For a minor offense, you have somebody who has a job, not making a lot of money, and then they can’t go to work, they’re going to be fired. It impacts society because if they’re not working, people still have to survive. They’re going to do whatever they have to do to survive.”

He’s already tackled the arrest problem with students, motivated by a Center for Public Integrity report released shortly after he took this job, in April 2015. The report documented the school to prison pipeline, when students end up in chronic imprisonment after minor infractions in classrooms.

“When I got that report I called my school staff and I said, how many kids have we locked up since Sept. 2014 to the day of that report? It was over 150-something kids,” he said. “They weren’t violent offenders, either. We were locking kids up for not sitting down in class, using profanity, and being disruptive. We were doing administrative duties for the school. That’s not our job, but we were put right in the middle.”

He acted quickly and came up with 14 categories of minor crimes that students can’t be arrested for. He says he might not be where he is today if police arrested students for the categories he’s identified. “I wasn’t sitting down in class. I was a knucklehead, but I didn’t get arrested.”

They try to help teenagers who routinely get referred to them with a nine-week program. “We teach everything from social skills, the use of social media, conflict resolution,” he said, listing components of the latest iteration of the program. It wasn’t always successful; they found that for many, the schedule conflicted with school and family needs, and transportation was an issue.

Now they pick kids up and bring them in on Saturday morning to prevent conflicts with school schedules. They follow-up at home and post-graduation. “I’ve hired a caseworker, and now we have all these service providers. We sit down with the parents. What do you need? And after they leave [the program] we keep tracking. We bring them in, we make them interns,” he said.

They use social media to reach youth, something they were praised for by the International Association of Chiefs of Police back in 2012. For Durham, it’s all part of community policing. Officers use social media apps like Nextdoor to talk directly to residents, and broadcast notices over Facebook and Twitter. They used the latter app as a primary point of contact during the neo-Confederate rally last September.

The Neo-Confederate Rally

Neighbors initially praised the response, but recoiled a little from sticker shock when the roughly $570,000 price tag was revealed. Durham stands by the cost as necessary.

“It was worth every dime spent,” he said, identifying the event as uniquely challenging to plan for.

The problem was the unknown. “Right after Charlottesville, we knew that the next event was going to be here,” he said, but police had no idea who or how many. “Nobody applied for a permit. We were in conversations with these folks, trying to [figure out the scope].”

The conversation leads him back to his time in D.C., where he spent most of his career, including eight years as an assistant chief in the Metropolitan Police Department. “Every day there was a protest, [from] one person standing in front of the White House with a sign to hundreds of thousands,” he said.

He supplemented his experience with research of similar recent rallies. One thing stood out to him right away. “In all those other jurisdictions, Charlottesville, Boston, and Berkeley, they were in public parks. We were talking about a residential neighborhood. Monument Avenue. Million dollar homes,” he said, highlighting the unique venue in Richmond.

One of the key lessons he took from videos was that banning armor, helmets, melee weapons, and pepper spray could reduce injuries. It was a move that led to some criticism from activists, especially at the pre-rally public safety meeting, where neighbors and residents asked how they could defend themselves. “My response was, ‘it’s our job to defend you’,” he said, recalling the debate.

Part of defending the citizens meant dealing with a lack of equipment and training in a city that doesn’t have the level of protests D.C. has. $84,280.85 went toward 75 body cameras. Nearly $25,000 went to in-ear communicators, necessary for keeping officers in contact over the half-mile zone that most of the activities would happen in.

Roughly $250,000 went to officer overtime for the 678-person police force, which has shrunk due to budget cuts. They needed training for protest situations, and, in the second consecutive year of a high homicide rate, officers available during the protest to handle regular crime. “I think it’s unfair to criticize police departments if this is the first time that they’ve experienced this,” he said, noting that these protests aren’t common in smaller jurisdictions. “It’s on the job training.”

While Charlottesville is still handling the aftermath of an event that claimed three lives and is the subject of multiple lawsuits, Richmond had a fairly calm event that dispersed peacefully, with no injuries and only a few arrests, primarily for wearing masks in public. “You plan for the worst, and the best happened,” Durham said.

The rally captivated headlines, but pales in comparison to the 57 murders committed with firearms this year. It’s a slight dip from the 61 murders last year, the highest in a decade, and seems to be following a national trend. Durham still identified marijuana as the major cause.

Richmond’s Homicide Rate

“Marijuana is the nexus,” he said, offering dozens of evidence photos showing scoped AR-15s, tactical shotguns, body armor, and in nearly every photo, bags and bags of weed. “That’s what’s driving our violent crimes, not heroin.”

Like his assessments on protests and community policing, he goes to the data. It’s less Reefer Madness, more The Wire, focused on the economics and policies behind crime. That data shows that police seized over 180,000 grams of marijuana in 2016, a four-fold increase over 2015, and twenty-times the amount of heroin, cocaine, meth, and hallucinogens combined.

“A lot of folks are being shot and murdered, because either one, they are going to purchase marijuana and they’re being shot and killed, or [two] they are are looking to rip off drug dealers. So, it’s a lose-lose situation for those folks,” he said. Suspect statements and text message records from cell phones recovered at crime scenes support his claim.

He wouldn’t offer an opinion on legalization. “That’s above my pay grade,” he said, before he shifted to decriminalization. “I think we have to look at the possession piece, because a lot of our young folks, that’s what we’re locking them up for. That has a disproportionate impact on people.”

He touched back on his concerns around criminal records. “We have young African-Americans smoking marijuana, then they get arrested for it. In DC, they decriminalized it. That will reduce the number of folks that we’re giving criminal records.”

The impact of drug-related violence has hit some communities harder than others. The six public housing properties administered by the Richmond housing authority, known as “courts” (Gilpin, Whitcomb, etc), are where most of the murders are perpetrated.

One of the proposals to address the problem, the controversial parking decal policy that would limit parking at the courts by requiring residents to apply for a limited number of decals, has been implemented in other cities. The plan, a collaboration between police and the housing authority, has been suspended by the new chair of that authority.

“The drug dealers come and set up shop in the public housing community for two or three days. You have these vehicles that come in and stay there, residents can’t even park, they’ve got to park blocks away from their home, and folks said, ‘we’re tired of this’,” Durham said, talking about the process.

The other factor behind the plan was support from the tenant councils, bodies of elected residents meant to represent their community. Durham was supportive of his partners in the effort, but acknowledged that the process didn’t bring in enough stakeholders, and expressed sympathy for the critics. “The messaging was not there, and when you just throw this up on people, hell yeah they’re going to be mad.”

Durham’s efforts against violence have a personal basis, too; he lost his younger brother to a senseless shooting in 2005. He’s fluent in the language of grief and tragedy, and has expanded departmental work with families of victims, even when the victim was a perpetrator shot by an officer.

“I do things that are unconventional. Whenever we have a use of force, I bring the families in, and I offer my condolences. Even the day of,” he said, talking about what sets the department apart. “If we have video [from a] body armor camera, I show it to them. Good, bad, or indifferent. I have compassion, I have empathy, and we’re not the same police department you see everywhere else.”

The department organizes dinners, social get-togethers, and field trips for families of victims; all part of the community policing initiatives that began back in 2005 under his mentor, then-Chief of Police Rodney Monroe. Durham served under Monroe as Assistant Chief from 2005 to 2007. Monroe’s policies were credited with reducing a high homicide rate, and Durham’s five-year plan, with a focus on community policing, seems to be working too.

“One of the things I’ve committed to is walking beats,” he said, referring to the neighborhood resource officers program, which placed its first round of neighborhood-specific walking beat officers in July. “Crime has gone down because of that.”

The numbers suggest his plan is working, but it’s little solace to Durham when talking about human lives. “Even today, our crime is down 2 percent, but that means nothing,” he said, noting that the homicide rate would be lower except for a few multiple-victim cases. “Last year, we had a 16 percent increase, now we’re negative 2, but that means nothing to those 50 families of those 55 victims, or those 255 folks that have been shot.”

Research suggests that national trends and income inequality are prime drivers of crime, making it unlikely that any police chief can prevent murders. Durham realizes this, but he knows he can still make a difference for the families of victims. “When [you lose someone], everybody’s there for you at first, for the funeral service, for a couple days after, they call you, [ask] how you doing. But after that, you’re not getting those calls. You’re still living it.”

He often cited numbers but, by the end of the interview, it’s clear that what really drives Durham is a deep sense of compassion for his neighbors, and a desire to be there for them on what might be the worst day of their lives.

*Photos by Landon Shroder