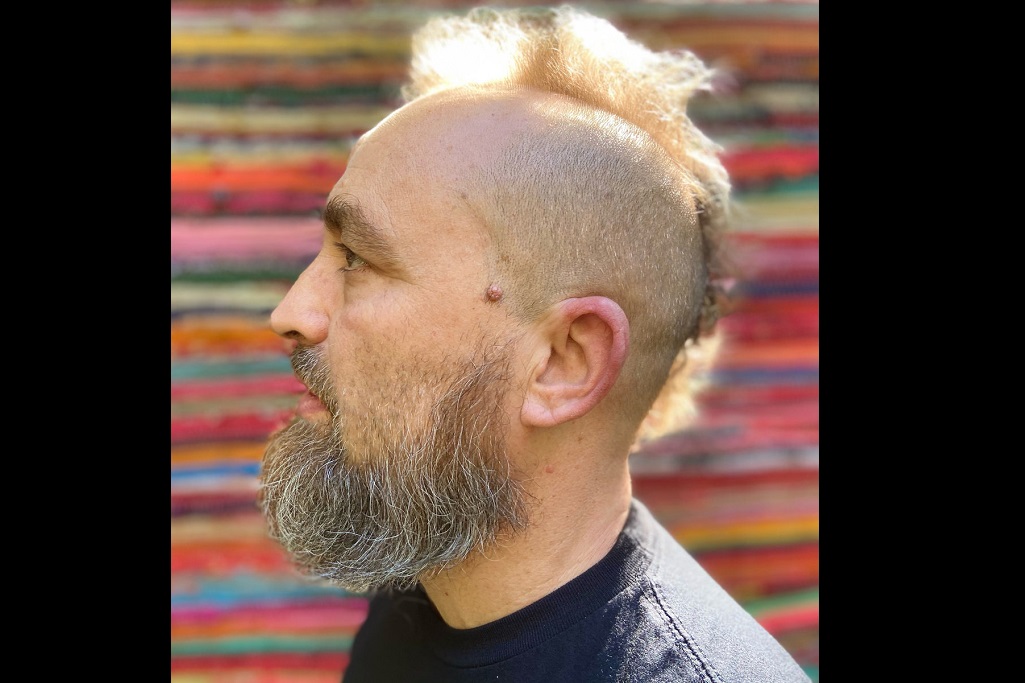

RVA Mag's own John Reinhold recently caught up with Shane Mitchell to talk shop about their shared experiences in music and creative events here in Richmond. Shane is also known as the producer be.IN; he is one of the founders of Ebisu Sound and an artist manager for...