The fifth installment in a monthly series in which a hometown Richmonder who has spent over a decade abroad explores the many different neighborhoods accessible by GRTC bus lines, to discover the ways transit connects us all.

Church Hill:

Strolling down the tree-lined avenues of historic homes, manicured mini-lawns, and tastefully curated porches of Church Hill, one could be forgiven for thinking they were out on a jaunt in Georgetown or Old Town Alexandria. Alas, a glance down 29th street toward the James River provides a reminder that this is still Richmond; the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument towers here over Libby Hill Park, one of the neighborhood’s grandest green spaces.

Upon this hill 282 years ago, William Byrd II — a notoriously cruel slaveowner — observed that this bend of the James reminded him of a view from his childhood, that of the Thames from Richmond Hill on the outskirts of London. The name of the neighborhood also derives from a nearby landmark: Saint John’s Episcopal Church. Within its four walls, Patrick Henry persuaded the First Virginia Convention to send its troops to fight the British with a cry of “Give me liberty or give me death!” If Church Hill is a neighborhood with a long memory, then its collective consciousness likely has whiplash from the rapid change that has swept across this part of the city over the past decade and a half.

This past March, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition released a study on gentrification and cultural displacement. In the report’s Richmond section, local urban planner Shekinah Mitchell documents the “racialized wave crashing onto the shores of neighborhoods” in the city’s East End like Church Hill.

In 2016, the number of black and white people in Richmond was roughly equal — clocking in at 47 and 46 percent, respectively, of the city’s population. This equalization marked a drastic shift from the demographics at the turn of the millennium, when blacks made up 57 percent of the River City and whites just 38 percent.

Beyond the identity crisis faced by similar cities once characterized by their large black populations, such as Washington, D.C. — dubbed “the Chocolate City” for this very reason — Richmond’s shrinking black communities are the canaries in the coal mine of widespread physical, economic, and cultural displacement. The southern chunk of Church Hill up to Broad Street has long featured mostly white residents; however, the area’s stock of charming, relatively affordable homes and increasingly expensive amenities like Alewife, WPA Bakery, and Dutch & Co. have drawn in ever-greater numbers of homebuyers with purchasing power beyond that of longtime residents.

Such rapid gentrification means the majority of homebuyers in black neighborhoods today are white people. The New York Times recently created an interactive map to document this phenomenon down to the census tract level. In the area increasingly marketed as Church Hill North, whites made up just one in four residents in 2012; yet over the period from 2000-2017, comprised 61 percent of those who received home loans. In Chimborazo and Oakwood, the numbers are more alarming still: blacks made up 83 percent of residents, but whites received 68 percent of mortgages.

New neighbors and amenities is a decidedly positive development for Church Hill. Gentrification need not be a dirty word: the problem with incoming residents is that all too often, the hunt for a place to live is a zero-sum game, resulting in a wave of displacement rather than a tide that lifts all boats. Historic district regulations and zoning laws frequently block the creation of more affordable multi-family housing, like the three-to-four story apartment buildings that make the Museum District so charming.

In this willfully sleepy neighborhood where bars close early and the sidewalks are still historic brick, it can be easy to squint and envision Richmond as it was centuries ago. The boxy, modernist homes springing up in every vacant lot are a preview of the city’s certain future. Whether neighborhoods like Church Hill — and Richmond at large — will grow denser or less diverse remains an open question.

The Ride:

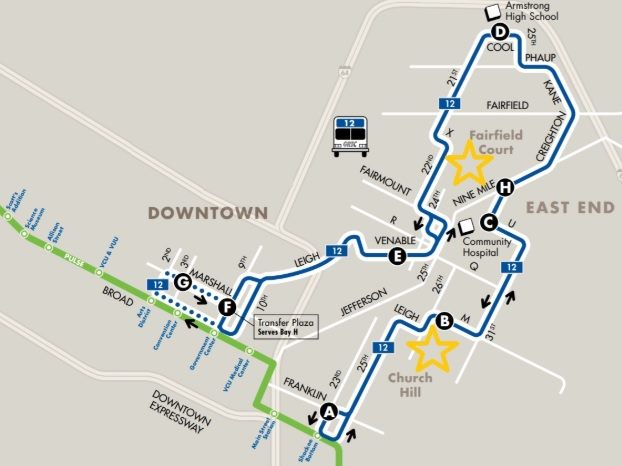

After gorging myself on both savory and sweet pies from Proper Pie Co., I stood at the corner of 25th and Broad waiting on GRTC’s Route 12 bus. A woman randomly walked up to me and asked if I needed a daily pass for the bus. She had accidentally bought multiple, not realizing that she could not activate the passes another day, but rather they were only good for the day of purchase. Thanks to the kindness of this stranger named Carrie, the ride was off to a good start.

Lacking active GPS data, the Transit app and GRTC’s app both showed the same arrival time. Yet no bus came. Instead of waiting thirty minutes for the next bus to possibly not show, my friend Amber and I decided to walk the ten blocks to the new Market at 25th. After exploring this corner of the East End, we walked to the stop at 22nd and Fairmount Avenue to see what the experience of a shopper headed back to public housing’s Mosby, Whitcomb, Fairfield, and Creighton Courts would be like.

Transit app had live tracking for two westbound buses. Buses on Route 12 are supposed to come every thirty minutes, but due to bunching, this day a westbound passenger would have to wait either 12 or 48 minutes between buses. There was no live data for eastbound buses at all. The first bus we wanted to take never appeared. As we waited thirty minutes for the next scheduled eastbound 12 bus, two westbound buses drove past.

After a half an hour sitting on the curb (this stop has no bench, shelter, or even a sidewalk), the next scheduled bus also failed to arrive. Frustrated, I tweeted at GRTC asking if something was wrong with the eastbound route. Their prompt response informed me that only two buses were running that day, and they had no information of any disturbances along the route.

During this final half hour waiting on the next scheduled bus, I witnessed both buses disappear from the Transit app’s tracking at Route 12’s westbound terminus and reappear in Shockoe Bottom, again heading westbound. After both buses passed our stop heading west a second time, Amber and I became too exasperated by the lack of a bus or answers, and gave up on the 12 — we took the Route 7 bus back to Church Hill.

For someone riding the bus simply to write an article, the failure of four buses to show presents an inexplicable inconvenience. For someone trying to get home after shopping with their family, this would be a disaster. Imagine sitting on the curb for hours with two kids in 98 degree heat, as all your refrigerated goods perished, and your bus home failed to come again and again.

The East End:

Wine tastings of bubbly rosés, fresh caught scallops, and shelves overflowing with rapini, Hokkaido pumpkins, and bok choy could not have been found in the East End just a year ago. For shoppers at the newly opened Market at 25th, such luxuries are becoming commonplace.

As we wandered through aisles named after East End churches, teeming with tons of products sourced from the greater Richmond region, the Market’s desire to make itself approachable to existing residents was almost palpable. The dozens of families packing their carts full on a Friday afternoon seemed to indicate all is going according to plan: for the first time in years, East End residents have access to healthy, affordable groceries at a full-service supermarket. Our conversational cashier concurred; after some initial growing pains and price adjustments, business has been booming.

A block down the road lies Bon Secours’ Sarah Garland Jones Center — another relatively recent neighborhood addition, which painstakingly pays homage to the first black woman who passed the Virginia Medical Board’s exam to become a doctor. Through a partnership with the Robins Foundation, the center is home to the Front Porch Cafe, a coffee house that equips East End youth with life skills and work experience while providing the community an inviting local place to gather.

Go a few blocks in any direction from these top-notch amenities and their placement in the East End begins to feel like an anomaly. Most other streets in this area feature at least one staple of what sociologists refer to as “urban decay”: abandoned homes, boarded-up storefronts, general blight. The poverty and neglect found here can feel so tragic and unavoidable to the untrained observer, but the East End was designed to fail.

It is no coincidence that four of Richmond’s six large public housing communities all lie within one mile of each other in the East End. Altogether, over 9,100 people call Richmond Redevelopment & Housing Authority’s Mosby, Fairfield, Whitcomb, and Creighton Courts home. Over half of the residents are children seventeen and younger; the rest are mothers, grandmothers, and mostly female guardians living below the poverty line.

South of Baltimore, RRHA’s four East End properties comprise the largest cluster of public housing in the country, and thus one of the densest concentrations of poverty in the whole nation, according to the agency’s outgoing head. What began as a New Deal-era ideal to replace slums with quality workforce housing rapidly transformed into a racialized weapon, to warehouse society’s least desirable people — blue collar blacks — in blocks of homes far away from wealthier whites. The six public housing complexes built for black people were never meant to replace the 4,700 housing units the city gutted from historically-black neighborhoods like Jackson Ward and Fulton, not to mention all the homes lost in predominantly black communities to the construction of I-95 and the Downtown Expressway.

In his book, Richmond’s Unhealed History, Rev. Ben Campbell writes, “You cannot separate the history of public housing in Richmond from race. It is the white establishment deciding what they want to do with predominantly black neighborhoods and using language that suggests they are trying to help improve them, while the actual fact is much darker than that. And that set the stage for what we are dealing with now.”

Today, that staggering concentration of poverty means 60 percent of Richmond’s public housing units fall within just one district, and thus have only one advocate for their needs on both a city council and a school board of nine. This intentionally diminished power of low-income voices manifests itself in the way we talk about, maintain, and plan the future of public housing today.

The courts’ maintenance issues and widespread lack of heat in past winters — many units didn’t have a functioning boiler last year — have led new RRHA CEO Damon Duncan to declare that Richmond’s current public housing properties have “exceeded their useful life by a good 15 years.” While current RRHA residents would likely jump at the chance to move into higher-quality housing, Duncan’s plans to demolish Richmond’s courts without guaranteeing current residents affordable units in new constructions has left many in the community worried displacement may soon be on their doorstep.

The boundary between Church Hill and the East End is as vague as it is porous. Although home values in the former may be triple or quadruple those of the latter, both neighborhoods face a similar challenge: how can we as a city welcome new residents without displacing those whose families have lived there for generations? If policymakers can’t solve this problem soon, then in a generation, there may not be much of a difference between Church Hill and the East End anyway.